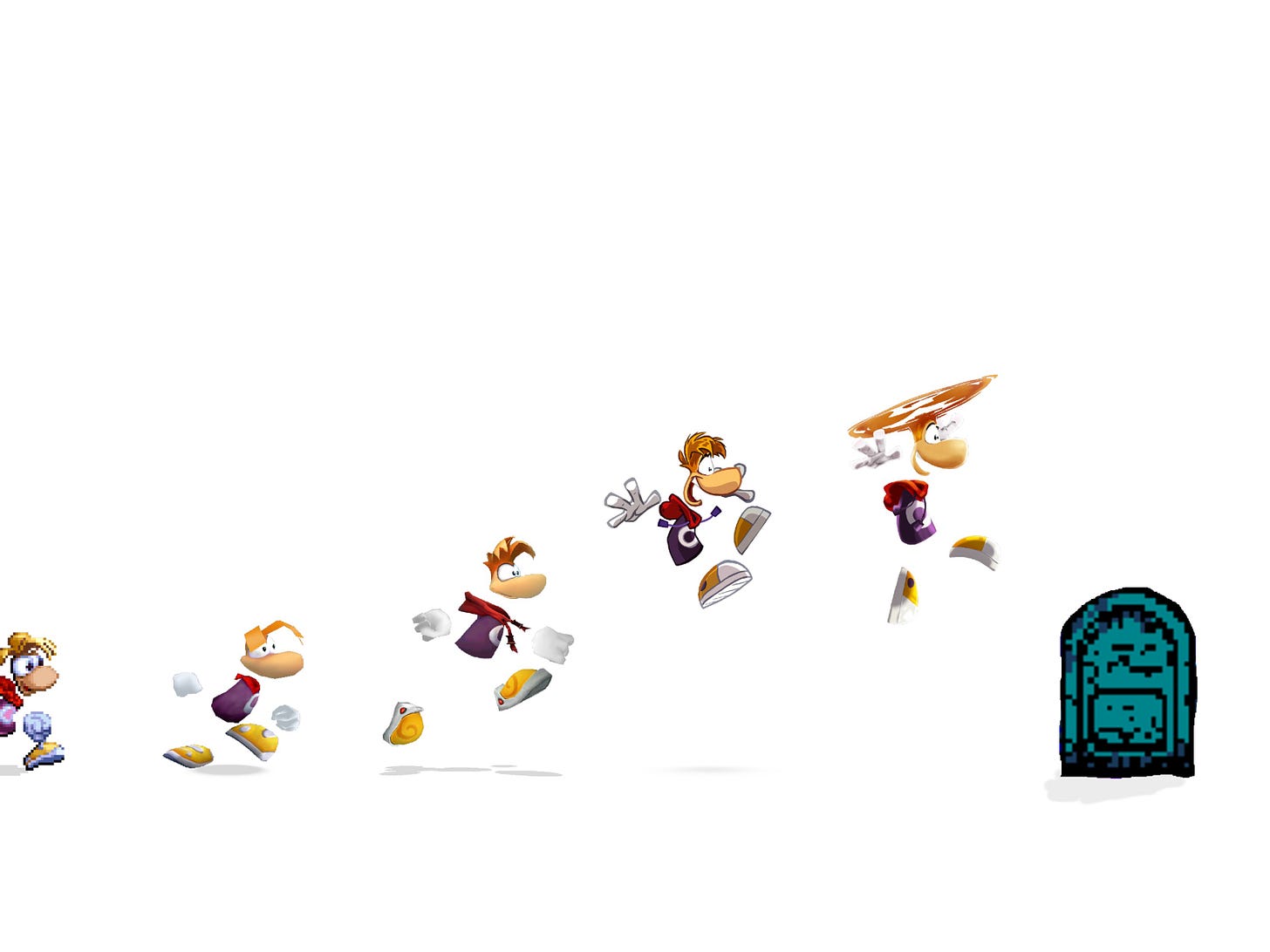

A Eulogy for the Video Game Publishing Titans (2000-2026)

Look upon my in-game purchases and despair

This week, Ubisoft announced it had canceled six games, including a remake of Prince of Persia: Sands of Time. The cancellations are part of a much larger corporate restructuring that will lead to a yet-to-be-shared number of layoffs. This follows last year’s restructuring and layoffs at Ubisoft, along with perpetual rumors that the company’s investors are interested in an acquisition.

Ubisoft isn’t the only publisher flailing its way through a precarious moment. To show some (perhaps undeserved) sympathy, what’s happening is far worse than the typical down-year of sales or generational shift in popular genres. What we’re witnessing is the end of a video game epoch.

Consider this its eulogy.

[This piece can be heard in the News of the Week segment in the latest episode of Post Games, The Untold History of Nintendo.]

In the early 2000s, the video game industry had consolidated around the power players that would dominate the early 21st century. Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft were the big three console makers. Video game publishing belonged in the West to EA, Activision, and Ubisoft. In Japan, Square Enix, Konami, and Capcom were the leaders.

By the mid-’00s, Blizzard would come to dominate the MMO space. And Valve would, by the end of the ‘00s, assert control over PC through Steam. However, the majority of games were still sold through brick-and-mortar retailers, namely GameStop. And thus, equilibrium.

For twenty years, these titans lived comfortably alongside each other. Occasionally, one would step over a line and into another’s space, like Ubisoft and EA building online gaming marketplaces of their own. But these aggressions would fail, and in short order, everyone would return to something resembling the status quo

By the end of the 2010s, some analysts, developers, and press began to sound the alarm. Habits were changing. Young people were playing fewer games, and what money they did spend went into free-to-play items and subscriptions. Then came Covid-19, and suddenly every adult who had ever given gaming a passing glance was stuck in their house playing everything from Animal Crossing to Call of Duty. The financial highs of the pandemic were a coat of paint over a moldy wall, and now, six years later, not only is the mold visible, but it’s also spread within the walls. The very structure is fucked.

The signs are especially dire amongst companies from the US and Canada. Some of these titans have consolidated, hoping to find comfort within mega tech giants to weather the oncoming storm. Others have sought protection from foreign wealth funds. All have taken shears to their portfolios, cumulatively canceling dozens of projects and laying off thousands of employees.

In Japan, things are, if not reminiscent of the golden, then at least stable, the industry benefiting from a surplus in creativity, and broadly speaking, a refusal to chase the ill-fated genres, like hero shooters, and monetization schemes, like games as a service, that undercut their western peers.

But all corners of the old guard are reckoning with the fact that their era is coming to an end, and a new era, with new established titans, has just begun.

This shift can’t and shouldn’t be tied to any one cause. And yet, if I had to pick a catalyst, it would be Minecraft, a game that was comparably cheap to create but offered unlimited space for creative expression. Its big-budget contemporaries chased cinema, prizing lifelike visuals, dramatic stories, and incremental power fantasies that placed players into the shoes of superheroes and supersoldiers.

The games of the new era would be established somewhere on this spectrum. Take, for example, Fortnite, which has the combat and intellectual property pizazz, while allowing players to build, destroy, and perhaps most importantly, style themselves as they see fit. Or consider Roblox, a game that saw kids accepting the visual simplicity of Minecraft, and discovered that aesthetic could be disregarded altogether. As could assumptions of quality. All that mattered, for millions of young players, was community.

It’s not new to say that these forever games are disrupting the status quo. What’s different is the industry-wide sense that the people in power at the old guard have no fucking clue what to do next.

Most publishers spent the past decade attempting to create their own versions of these money-printing machines. But they have failed. The CEOs, the investors, and the game directors learned the hard way that putting hundreds of millions of dollars into these games guarantees nothing. Over the past five years, Ubisoft’s stock value has dropped 90%.

I don’t know what comes next. In a recent interview with Stephen Totilo at GameFile, the CEO of Nexon, Junghun Lee, spoke about the incoming third wave, one that may even threaten the Robloxes and Fortnites of the world:

“The boundary between our everyday life and games is becoming more and more blurry, and they’re kind of torn down. So, I thought maybe that could be a fun kind of space, an area where we can gain some great clue towards what will be the next fun experience.”

Maybe the old guard will run in this direction, whatever it might be. Or maybe they will do what so many former titans have done in the past. Run out of ideas. Look for ways to cash out, through painful layoffs and hurried acquisitions. And disappear.

In 1980, Atari was unstoppable. By 1984, it was practically dead. It’s the perpetual reminder to an industry led by a narrowing list of absurdly wealthy CEOs, that even the biggest monuments will turn to dust. And so, don’t be surprised if years from now you stumble upon an ancient press release that reads, “My name is Bobby Kotick, King of Kings: Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” And you find yourself asking, “Who the hell was Bobby Kotick?”

[Enjoy this post? Subscribe to the Post Games podcast and hear this story along with weekly interviews digging into the most pressing and interesting topics in gaming.]

Good post is good. What a weird time.

Nailed it. And totally agree Minecraft was the harbinger of a much bigger wave